|

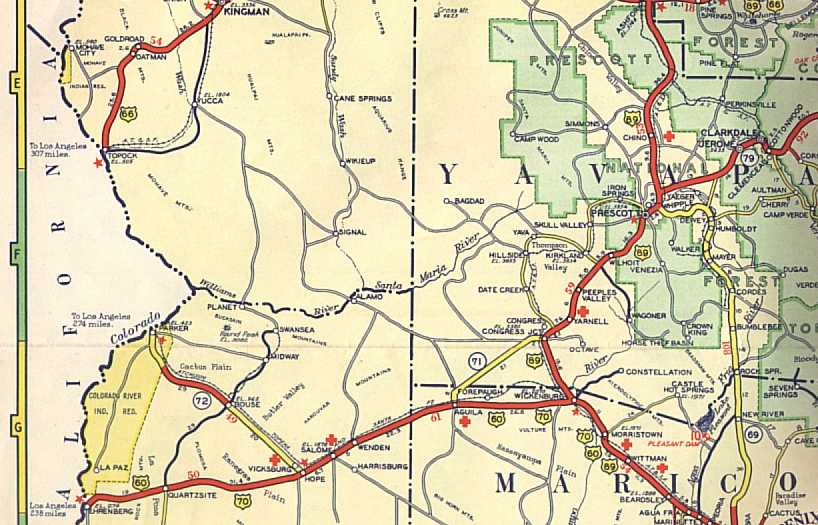

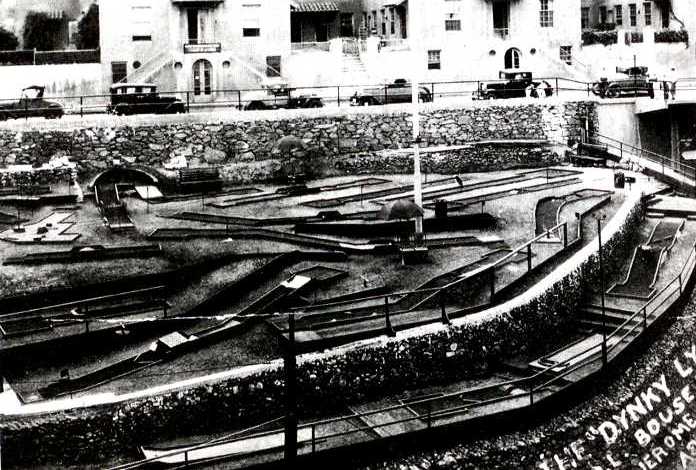

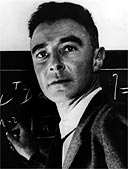

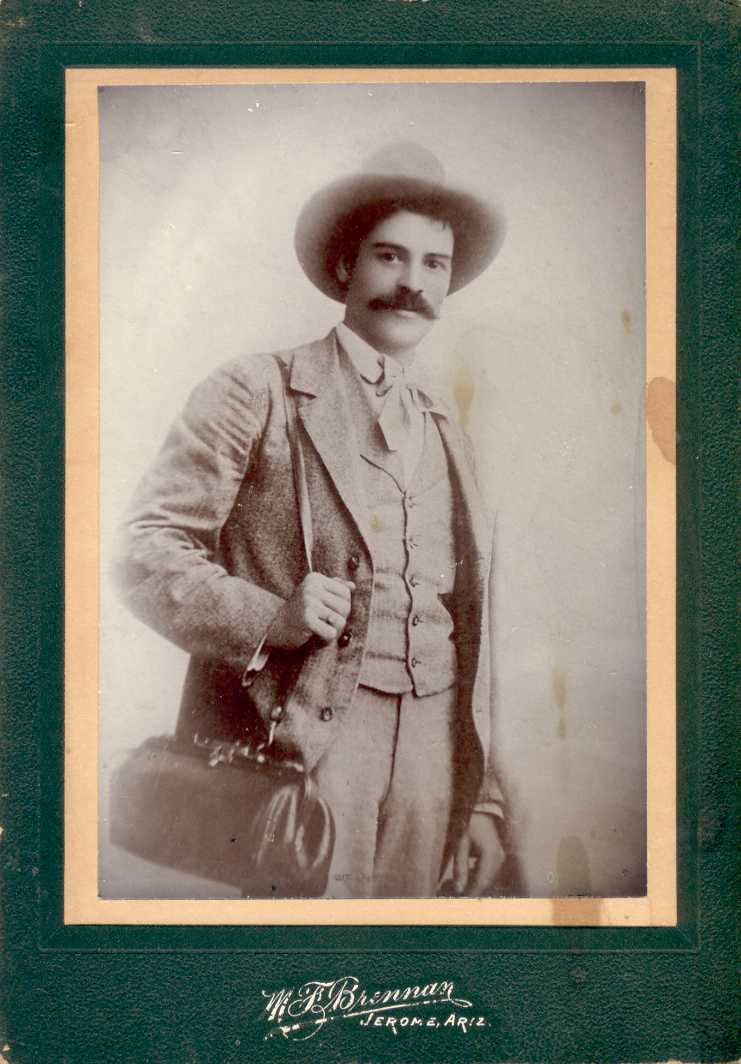

On a whim, he had taken the southerly route along highway 60 which had taken him through Blythe, on in to Aguilla. From there he hooked up with 71, which turned out to be all gravel, and then 89, which took him through Prescott and finally into Jerome. He usually drove route 66 over to Albuquerque to get to the ranch, but he had decided that he needed a change of scenery. He thought that some new landscape might help to inspire some fresh ideas.  He was particularly perplexed by the implications inherent in the new theory by Zwicky and Baade concerning collapsing supernovae. With Chadwick's discovery of the neutron, it seemed as if they might be on to something. Of course, Zwicky's grasp of quantum mechanics was a little shaky, but, none the less, if one followed the meaningful thread of the theory to its logical absurdity, the implied consequences were staggering.  When he reached Jerome it was already about four pm. The drive had taken more time than initially calculated, so he decided to get a room for the night and continue on in the morning. As he pulled into town, he was immediately struck by how subdued it seemed. By the number of houses and businesses and large structures such as schools and hospitals, he would have judged it to have a population in the thousands. But as he drove into what must have been the main business district, the place almost seemed deserted. As he parked on the main street, he realized that he had pulled right in front of a hotel called the Bartlett. It was a large two story, stone and masonry structure that housed not only the hotel but a small bank as well. He checked in at the desk, carried his small bag upstairs to the room, surveyed his accommodations, found them adequate, walked back downstairs, out onto the sidewalk, and began to stroll through the business district - all the while meditating on collapsing stars. He barely noticed his surroundings. Ideas were much more fascinating. When Chadwick discovered the neutron in 32, it was just what Zwicky needed to calculate that if a star could be made to implode until it reached the density of the atomic nucleus, it might transform into a gas of neutrons, reduce its radius to a shrunken core, and, in the process, lose about 10 % of its mass. The energy equivalent of the mass loss would then supply the explosive force to power a supernova. Baade and Zwicky predicted that this collapse would strip the atoms of their electrons, packing the nuclei together as a neutron star. These would be only 10-15 miles in diameter, with densities on the order of a billion tons per cubic inch. The scientist pulled his pipe from the inner pocket of his Macintosh, packed it with fresh tobacco, and lit it with his lighter. He chuckled as he wondered how Serber was doing. Probably, pulling his hair out. Every month now there were new breakthroughs and fresh understandings concerning the universe - from the largest stars to the smallest sub-atomic particles. The fields of quantum mechanics and nuclear physics were developing so rapidly that it tended to make even the most sober and responsible scientists light headed. They said Teller had taken to wearing shoes that were too large for him, because he was afraid that the spaces between atomic particles were so vast he might fall through the floor. Actually, it was Teller who told him about Jerome in the first place. Apparently, he had passed through the town a couple of weeks ago when he got lost on one of his mountain climbing expeditions. As he walked along the sidewalk, he looked out across the valley. The sky was as gray as slate. The red rock cliffs on the other side of the valley seemed dull and lifeless. The hills around the town were brown and barren. What few trees could be seen were leafless. The air was crisp - not as cold as it probably would be at the ranch, but cold enough to wear a jacket. The date was October 12. Normally, the weather would have been much balmier. Hot even. This was an early cold snap. Within a few days the temperatures would probably be back into the seventies. Just below him was a miniature golf course. It seemed odd the have this attraction right in the middle of the town. He thought that the space could have been used for something more useful.  He stopped and surveyed the destruction. He surmised that there must be some kind of geological fault on that side of the street that had given way under the weight of the buildings. Intrigued by the unusual situation, he sat down on a bench in front of Krotinger's and puffed away on his pipe. As he examined the decaying buildings, his thoughts went back to the implications of Zwicky and Baade's theorizing. The streets were unusually quiet. It seemed as if it were a Sunday morning. There were very few people on the street. No traffic to speak of. He appreciated the quiet. It allowed him to think. Unfortunately, the silence was broken by the sound of a radio. Above him and to his right, President Roosevelt was starting to address the nation with one of his fireside chats. The sound drifted out an open window on the second floor of Jewelry Shop next door. The thinker was too absorbed in his meditations to pay attention. He had stopped listening to FDR's soothing bromides and policy propagandas.  Looking at the sinking buildings across the street, he realized that if he sat there long enough, they would disappear from view, slowly sucked down by the gravitational forces at work. The far edge of the street became a kind of horizon below which nothing could be seen. A sudden illumination came to him. It struck him that what Schwarzchild saw as a singularity as a star collapses was not that at all. Schwarzschild's radius r*=2m was not the singularity itself but rather the "horizon" from which nothing, not even light, could emerge. It followed then that as the star collapsed the contraction would continue indefinitely. It would collapse through the Schwarzchild radius. He sat there with Roosevelt's voice droning in the background and let the implications sink in. He felt as if he had gone through the looking glass. The energy and mass had to go somewhere. It was an inviolate law. But where the hell did it go? Into another universe? Did these collapsing stars create doors into another world? Where there collapsing stars in that world that spewed matter and energy into this one? None of it made any logical sense.  " . . . but we know that if the world outside our borders falls into the chaos of war, world trade will be completely disrupted. Nor can we view with indifference the destruction of civilized values throughout the world. We seek peace, not only for our generation but also for the generation of our children. We seek for them the continuance of world civilization in order that their American civilization may continue to be invigorated by the achievements of civilized men and women in the rest of the world . . . " As much as the politicians spoke about peace, the scientist knew that war was coming. Hitler was mad and would not rest until he lived out his insane visions. Anyone who thought any differently was deluding themselves. The madman had already forced some of his relatives to leave Germany simply because they were Jewish. It was not a question about if there was to be a war, only when and how large and how long. Global events seemed to generate their own gravity, and, when they reached a critical mass, there was no way to stop them from the fall. The ambitions of Germany and Japan were going to suck the world into a violent whirlpool of catastrophic proportions the outcome of which could not yet be seen. The only certainty was death and destruction. The world was being drawn into a dark abyss - a sucking black hole from which nothing could escape.  Roosevelt had finished his speech and the radio station returned to playing music. A new melody drifted out onto the street. It was something that he hadn't heard before. He noticed an old man walking toward him down the sidewalk from the direction of the hotel. He walked slowly with a slight stoop to his posture. He wore a long gray overcoat and matching fedora. A blue plaid wool scarf was wrapped around his neck. As the music played, a man started singing. It was Fred Astaire. The scientist recognized his voice immediately. He was a fan. Fred was singing something about "they can't take that away from me". As the older man approached, their eyes met and the other man smiled. "Afternoon, young man," he said affably. "Good afternoon," he replied. The man stopped, looked across the street to the collapsing buildings and then back to the younger man. "You seemed pretty deep in thought." The scientist chuckled. "Yeah, sometimes I think I think too much. Tend to tie my brain in a knot." It was the other man's turn to chuckle. "I have done that a time or two. The result is usually a headache." He extended his hand. "Charles Woods," he said. They shook hands. The older man's grasp was warm and firm. "Robert Oppenheimer. Pleased to meet you."  As he looked in the older man's eyes, he realized the he was of mixed blood. He seemed to be part Negro, perhaps part Indian, and part Caucasian. Oppenheimer made him to be about six feet tall, about two hundred pounds. His face was deeply lined and his eyes had a slight yellow cast to them. He had a strong nose and chin, and sported a thick mustache that had been stylish in an earlier era. His was the face of a man who had made his own way in the world. It was a face that would command respect. "You live here?" Oppenheimer asked. "I have lived here the past forty years," he said. He spoke slowly and formally, as if he was from another era. "It is sad for me to see it come to this." He gestured across the street to the destruction. "Do you - or did you work in the mines?" "No . . . I am a doctor. I was the surgeon for the United Verde Mining company until nineteen hundred and six. I have had my own practice for the last thirty years." He looked back to Oppenheimer. "And yourself, Mr. Oppenheimer. What is your occupation?" "I'm a physicist - a teacher - over at Caltec. I'm on my way to my ranch over in New Mexico. Took a different route and ended up here. It's quite an unusual town." "You should have seen it when it was booming. Fifteen thousand people lived here not ten years ago. The mine operated twenty-four hours a day. The streets were full of people - full of life. I would venture to say that you have never seen anything of its kind." He smiled warmly then at the memory. "The owners closed the mine in nineteen and thirty one and most people relocated. Now, the town is dying. They reopened the operation in thirty-five and are mining a bit more these days now that there is a war coming, but the ore body is no longer yielding anything of a high grade." "So you think the war's inevitable?" Dr. Woods looked him briefly in the eyes. "I would think it was obvious to anyone paying attention." Oppenheimer could sense the man's sadness and sense of loss. He and his world were old and dying and there was nothing he could do about it. Without warning an earsplitting blast shattered the silence. Fear shot through Oppenheimer. It sounded like a bomb. He cringed and clutched tightly to the bench. The earth beneath their feet shook and felt loose. The buildings around them rattled and groaned. Oppenheimer heard the large plate glass window behind him rip, a crack slicing diagonally across its face. He jumped up from his bench to escape the potential flying glass. The ground was still quivering. He heard some kind of large beam or structural member snap in one of the sinking buildings across the street. A large puff of smoke rose in the air above the rear of the structure. He looked over to the older man who was trying to steady himself but did not look disturbed or frightened. As the rumble died away down the canyons, Oppenheimer almost screamed. "What the hell was that?!" "They are blasting out at the mine," Dr. Woods replied. "That was a particularly large explosion. Perhaps a quarter of a million tons." "A quarter of a million tons of what?" "Of dynamite, Mr. Oppenheimer. They are blowing the mountain apart trying to get the last of the ore out." Oppenheimer just stared at the man. It took him a minute to find his voice. "But look what it's doing to the town! What are they - " The scientist was dumbfounded. He couldn't understand. Exploding a quarter of a kiloton of explosives within a tenth of a mile of businesses and residences seemed mad. He realized that he was still staring at the other man. Dr. Woods nodded ruefully. "They want the copper for the military." Having lived in California for the past few years, Oppenheimer had experienced his share of small earthquakes, both in the Bay area and Los Angeles, but he had never felt one that large. It must have registered at least a seven on the Richter scale. His nerves slowly settled down, and the adrenaline stopped pumping through his system, but he remained stunned by what he had witnessed. He looked with a new appreciation at the devastation across the street. It must have been going on for months. One entire three story building had already completely collapsed. Others, still somewhat intact, were slowly sliding down the hill. A J.C. Penny store had built new stairs down to its front door which was now four feet below the sidewalk. They were still open for business.  The old man spoke. "It will be up to you." Oppenheimer came out of his reverie. "What's that?" "It will be up to you and people like you when the war comes." The scientist looked over to the old man who was still staring at the destruction across the street. "What are you talking about?" asked Oppenheimer. "You say that you are a scientist?" "That's right. A physicist." "It will take acts of madness to stop the madness, I believe. You are going to have to fight fire with fire." Oppenheimer looked more closely at the man. Perhaps age had addled his brain. He seemed to be on the verge of incoherent rambling. The younger man began to feel a certain pity for Dr. Woods. "I'm afraid you must be confusing me for some other kind of scientist. I'm strictly a theorist. Quantum mechanics. Nuclear physics. I seriously doubt if any of my work would be able to help the war effort." Woods looked over at him with a slight smile on his face. As they looked at each other, Oppenheimer realized that the look on the Doctor's face was one of compassion and pity. For some unknown reason the older man was pitying him. "I am sorry," said Woods, "I did not mean to presume . . ." He seemed to drift off and his eyes took on a look of distaste and pain. " . . I . . . I have seen things . . . " . He seemed to struggle within himself, as if something was trying to pull him down into a dark hole. Finally, he appeared to get the upper hand. The doctor came out of it and smiled. "Please, excuse the musings of an old man. I did not mean to intrude upon your day. It was a pleasure meeting you. I must be on my way. My wife will be wondering . . . " Oppenheimer felt bad. He felt as if his reaction was driving the older man away. He wanted to say something to make him stay, but instead, he just extended his hand and they shook. "The pleasure was mine," said the physicist. He smiled and tried to ease the tension. "We wouldn't want your wife to worry." "I am afraid that there is no way to prevent that," said Woods, and they both chuckled at the anxiety of women. Woods tipped his hat, smiled, and winked. "Fare forward, Mr. Oppenheimer." Oppenheimer watched as the old man slowly walked down the sidewalk and into what appeared to be a residential neighborhood. As the man disappeared around a curve in the street, his final words struck Oppenheimer with a delayed reaction. "Fare forward"? Not farewell? That was odd, and yet somehow familiar. He stood there a minute and tried to remember where it was that he had heard that phrase. Suddenly, it came to him. He had read it in the Bagadavita. When Krishna admonishes Arjuna on the field of battle. Not farewell but fare forward. He wondered if the old man knew that. If he had read the ancient Hindu text. He shook his head and dismissed the thought. The poor old doctor was probably just a little off. A little senile. He sat back down on the bench in front of the hardware store and pondered the older man's words. He realized that he had not seriously considered what would happen if war did come. He had thought about it intellectually but he hadn't let the ramifications sink in. He hadn't thought what it would mean for those he loved, for students who might have to leave the universities to become soldiers, for associates whose children might have to die in the fight. For wives who would lose their husbands, children their fathers. A great sadness came over him. A sadness for the entire human race. How could it be that humans had lived on the planet this long and it could still come to this? He looked out across the street to the collapsing buildings and beyond. The sun had gone down and it was starting to get dark out over the valley below. A few cars drifted down the street in front of him. He guessed that people were getting off of work from the mine. A tall, lanky man with thinning brown hair and wearing a fitted vest came out of the door of the tailor's shop to his left. The man came over, said hello, and examined the new crack in his plate glass window. "Damn it! That's going to cost. Sons a bitches!" "How long has that blasting been going on?" Oppenheimer asked. "Ever since they reopened the mine two years ago. I suppose I should be thankful that I didn't open across the street like poor Kovachovich." He looked over at the gaping hole where there used to be a thriving business. "If they keep it up, this whole damn town's gonna slide down the damn hill." "Doctor Woods was telling me that the town used to really be something - that there used to be fifteen thousand people living here." The tall, thin man looked at him oddly. "Who?" "Doctor Woods? Charles Woods?" The man stared at him with his mouth slightly open. "Oh yeah, Doctor Woods. Well, gotta close up. Take care." The man turned and walked quickly back into the store. Oppenheimer thought his reaction was odd but his growing hunger was occupying more of his attention. He had noticed that there was a restaurant down the street from the hotel where he was staying and decided that it was time to have some supper. He stood up from the bench, relit his pipe, and headed back in the direction of the restaurant. Inside the shop, Harry Krotinger walked over to his wife, Charlotte who stood behind the counter, taking money out of the cash register and putting it in a lock box. She was a pleasant looking, chubby woman in her fifties, wearing a simple, flower print, cotton dress. Her graying hair was cut close to her head in a wave. She looked up through her rimless glasses as he walked up. He appeared to be agitated. "See that guy?" he asked, pointing to Oppenheimer. "Yes. What about him?" "He said he was just talkin to Doc Woods." Her eyes went wide and her skin turned ashen and she quickly crossed herself with a shocked intake of breath. "Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, Harry! That's the second stranger in two weeks." "I don't like it. It ain't no good. It's like a bad omen." Mrs. Krotinger came out from behind the counter and walked over to the plate glass window. "Lord. It's un-natural. That's what it is. Gives me the willies." Her husband followed her over to the window and watched as the stranger walked across the street. He was tall and thin, wore a macintosh and a floppy fedora. He was smoking a pipe and sauntering along as normal as you please. "You didn't tell him?" the wife asked. "You think I want to get into that conversation again? You saw what happen to the last guy. He about took my head off, arguing with me." "Yeah, he got all twisted up . . . " They both continued to watch Oppenheimer as he walked past the Bartlett, and then she asked, " . . . Wasn't that guy the one that bought those shoes that were three sizes too big?" "Yeah, that was him. Had a wooden left foot. Funny little guy with a German accent." "Yeah . . . funny little guy . . . " The Krotingers watched the stranger walk into the restaurant before they turned to look at one another once again. The husband and wife both spoke at the exact same moment. "Let's sell this damn place," they both said. Robert Oppenheimer went on to become the director of the Manhattan Project during World War II and is well known for being the father of the atomic bomb. In 1939 he published two papers, one with George Volkoff, and the other with Hartland Snyder. Both were concerned with gravitational collapse, the predicted fate of a massive star after its thermonuclear fuel was burned up. These papers became the basis for the discovery of black holes.  Photo of Charles Winter Woods as a young man. Courtesy Jerome Historical Society "He was born in Tennessee, but spent his youth in New Orleans, where he became a driver for and an aide to a Doctor. He showed such adaptability that his employer encouraged him to take medical training. He did take a short course in medicine and surgery in a New York eclectic college. Woods was an Octoroon, and he felt he would find better acceptance away from the South. He came to Arizona. He had not yet become located when in 1892 he found work as a laborer on a freight transfer gang at Jerome Junction. when a workman had a leg crushed in an accident, Woods took charge, amputated the leg, and did such a good job of it that H. J. Allen was impressed, brought the young man to Jerome and placed him in charge of the United Verde's new hospital. It was said that Allen had to use his considerable influence in Phoenix to persuade the territorial medical board to issue him a certificate to practice, but a few years later Woods was appointed to membership on the Board. He remained United Verde's chief surgeon until 1906. He then set up a private practice, which he pursued in a rather desultory way. He was married to Elvia Fazell, a San Francisco opera singer, musician, and orchestra conductor of French training. She survived him." From "They Came to Jerome" by Herbert V. Young Jerome Historical Society 1972 "Garlic and sapphires in the mud Clot the bedded axle-tree. The trilling wire in the blood Sings below inveterate scars Appeasing long forgotten wars. The dance along the artery The circulation of the lymph Are figured in the drift of stars Ascend to summer in the tree We move above the moving tree In light upon the figured leaf And hear upon the sodden floor Below, the boarhound and the boar Pursue their pattern as before But reconciled among the stars." From "Burnt Norton" by T.S. Eliot 1935 |